How we’re using data about goats to empower women and raise incomes in India

Using data-driven practises and trends, AKF supports Indian communities to double their incomes

In Bihar, India, around 3 million households rear goats. 96% of these households are landless, making goat rearing – an activity that does not require substantial land – a key source of supplementary income for many. Goat rearing is largely done by women, who often lack access to veterinary services and have limited knowledge of animal husbandry practices such as feeding, housing, management and marketing.

In response, the Aga Khan Foundation (AKF), supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation began training women as animal health workers (pashu sakhis in Hindi), to provide preventive health services to goats.

Since 2016, AKF has trained over 350 pashu sakhis in Bihar who provide veterinary services to over 70,000 female goat rearers.

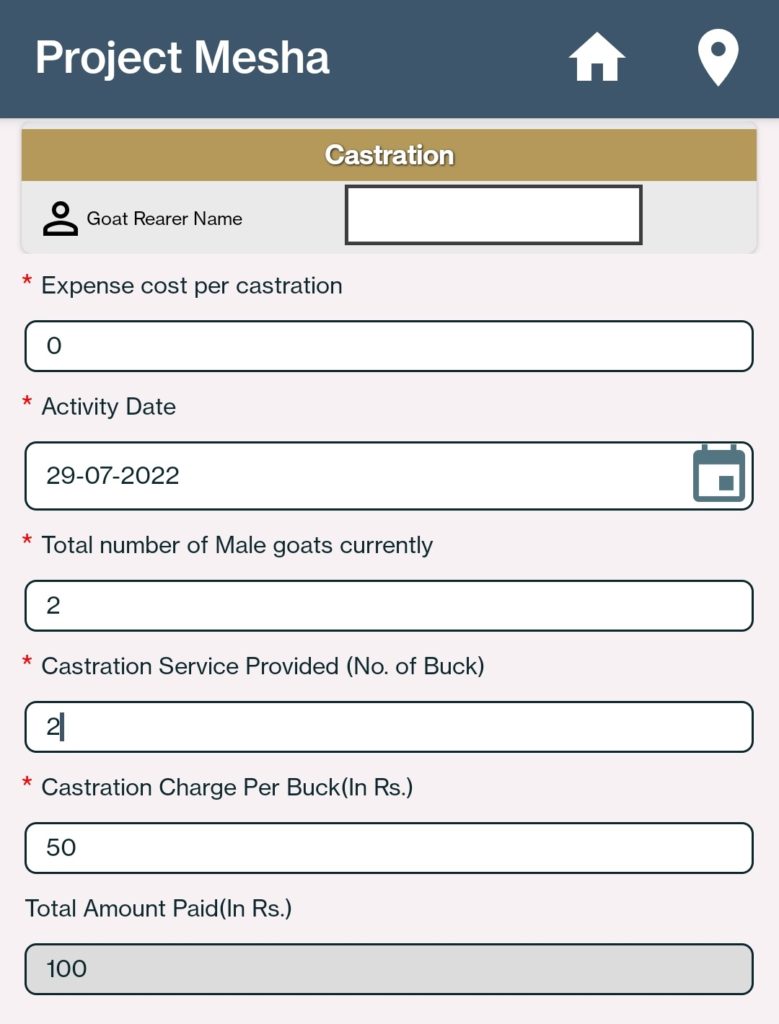

In order to keep record of the services provided and the income generated from them, AKF equipped the pashu sakhis with tablets and a custom-built mobile data collection application that enables real-time monitoring and data management. The app’s interface functions both in Hindi and in English.

After each service delivery, pashu sakhis enter data about the goat rearer, which service they provided, and how much they charged. The data is then submitted and reviewed for quality assurance and validation by AKF.

Through this data, analytics are generated that provide insights on:

- How many services were delivered?

- Which type of services were most commonly delivered?

- How much profit did pashu sakhis make from delivering services?

In 2019, the AKF team met with pashu sakhis to review, analyse and interpret the data that had been collected so far. When reviewing the data, an unexpected trend emerged.

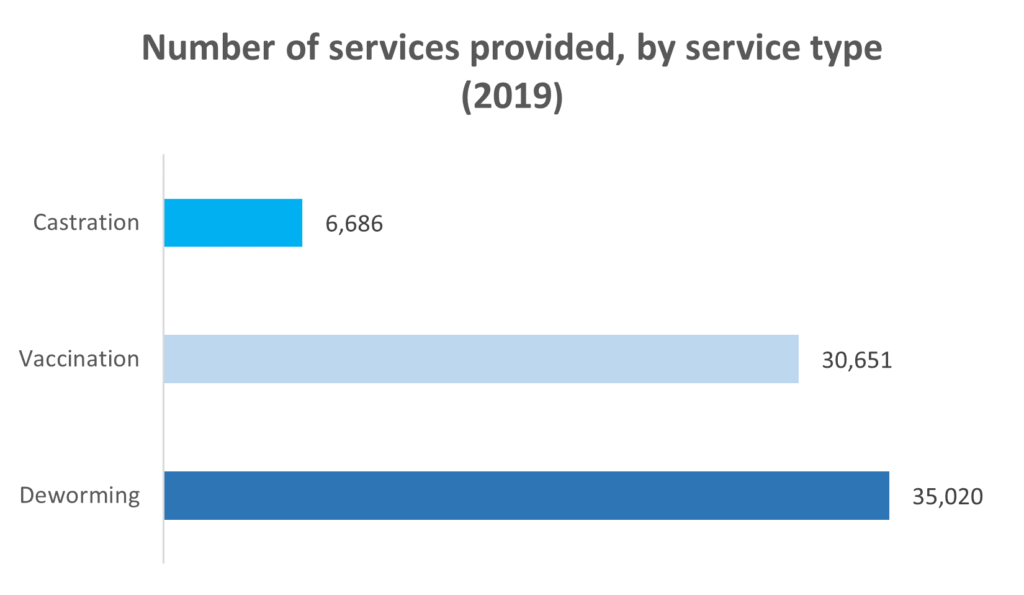

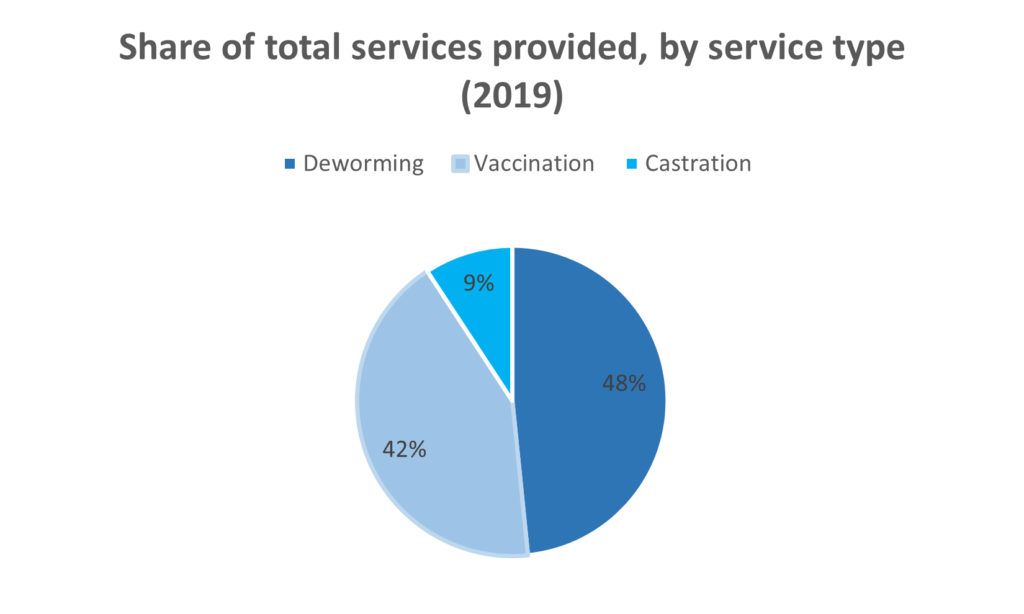

Of the 72,000 services that pashu sakhis had provided in 2019, 48% were deworming, 42% were vaccination and only 9% were castration.

This finding was perplexing. While the number of castration services were expected to be less than the other services (castration is a one-time service, only for male goats) the numbers were significantly lower than expected. Pashu sakhis charge 50 Indian Rupees (approximately 63 cents in US dollars) per castration, a rate that is 80% higher than vaccinations and 84% higher than deworming, so it was surprising that they were not offering this service more widely. There was also demand for castration services among the goat rearers. Castration aids in faster growth and yields higher financial gains when it comes time to sell – facts widely understood and accepted by goat rearers in the community.

This finding posed the question – why were pashu sakhis reluctant to offer this service?

Several challenges were raised by the pashu sakhis in their discussions with the AKF team:

- Compared to the other services offered, castration requires a high degree of technical skills

- The pashu sakhis expressed that they did not have a high degree of confidence in their ability to provide this service

- Some goat rearers and other community members felt that the approach pashu sakhis took to castration did not align with cultural norms, since they were women performing castrations and using modern castrators as opposed to the traditional knife method

To help resolve this issue, AKF provided intensive support to the newer pashu sakhis through more demonstrations to build their confidence and technical capacity. AKF also shared data in monthly review meetings to demonstrate the potential of increasing their income if they focused on castration services in a planned way. AKF also began working with goat rearers to convey the benefits of the ‘pashu sakhis’ modern approach to castration – how it was safer and more hygienic than traditional approaches.

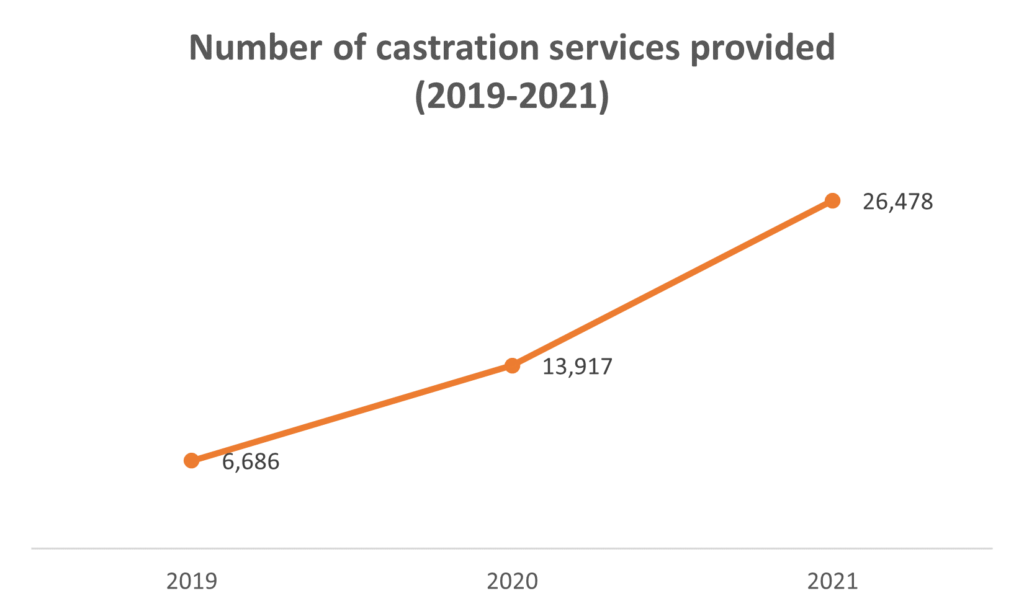

A dramatic change was observed in the following years. The number of castration services rose by 108% in 2020 and again by 90% in 2021. This resulted in an increase of over 1.3 million Indian Rupees (approximately 17,000 US dollars) of revenue – an average of 6,700 Indian Rupees (approximately 85 US dollars) per pashu sakhi over two years.

The biggest lessons from this experience?

- Data gave AKF a concrete basis for starting conversations on the trends that were emerging from the practices being applied by pashu sakhis.

- Interpreting data with those from whom it was collected (the pashu sakhis) proved to be a powerful way to understand the meaning behind the trends in the data.

- Data helped AKF and the pashu sakhis to visualise and understand the opportunity cost of focusing on mainly on deworming and vaccination services and how outcomes might differ if alternative choices were made.

This article was written by Rumani Chakraborty, Programme Officer, Monitoring and Evaluation and Amanda Sullivan, Global Data and Insights Manager, AKF.

Support our work Your donations are helping us build a future where we all thrive together.