Climate Resilience

How solar energy is helping this Syrian village become more climate resilient

Harvesting olive oil wasn’t always so difficult for Munzer Zidan (pictured above). The farmer and retired teacher from Khirais village in Syria owns 175 olive trees. Previously, he was able to produce 12 tanks of olive oil annually, which became his primary source of income.

This year, Munzer’s harvest was insufficient to fill a single tank of olive oil.

“The rain has dropped dramatically, especially over the last three years, and this has impacted our ability to irrigate our crops,” he said in an interview.

And Munzer is not alone. His neighbours, also farmers, are experiencing similar challenges in the tiny village comprising 24 households. Residents say consequences of a changing climate, including the country’s multi-year drought and unpredictable weather patterns, have caused a drastic reduction in their agricultural productivity.

Between a multi-year drought, unpredictable weather patterns, and climactic shocks such as earthquakes, smallholder farmers in Syria, such as Suliman Zidan, are becoming increasingly food insecure.

For farmers like Munzer, this means a loss of income, which is particularly challenging given that Syria is currently experiencing one of the worst economic crises since the start of the civil war in 2011. Families face food insecurity as they struggle to harvest crops on their land, which they previously relied on for sustenance.

One of Munzer’s neighbours, Suliman Zidan, a community leader and a farmer, said access to water has been his primary concern. Alongside other community members, Suliman was digging wells to increase water supply.

“We were digging because of the drought. We tried to dig until we reached [ground water] so we could irrigate our crops,” Suliman explained.

Then, the devastating earthquake hit Syria in February and Khirais was badly affected.

“[Our progress] was destroyed in the earthquake, and we had to start all over again,” he said.

Syria’s multi-year drought has led to a food crisis, leaving 12 million people food insecure.

According to Bakhtiyor Azizmamadov, Programmes Director at the Aga Khan Foundation in Syria, climate change has had several other catastrophic impacts.

The ongoing drought has led to unbearable heat waves. It has contributed to crop failure and livestock losses. And there have been large-scale displacement and migration of rural populations as farmers and herders have moved to urban areas in search of economic opportunities.

“There is continuous water scarcity. There are several key rivers which are experiencing reduced water flow, which is impacting livelihoods — particularly food security [and] agricultural production,” Azizmamadov said.

Life used to be easier. We never used to worry about food.

Rebuilding Khirais amid unreliable energy access

In 2021, community members began rebuilding Khirais which had been badly damaged during the country’s civil war. They removed landmines, repaired homes, planted trees, and revived agricultural projects.

As the villagers worked to revive their community, a prominent challenge arose — accessing reliable and regular electricity.

“It was three hours on and three hours off,” Munzer said of the village’s frequent blackouts. “This was sufficient for us to use washing machines and manage our refrigerators, but now the [power supply] is only one hour a day, and it is not sufficient for us to do anything.”

With reliable access to electricity, Ruba Abzo can now process milk and cheese, sourced from her family’s sheep and cows. Her small business has increased her family’s income, helping them afford basic necessities.

Residents had to adjust given the limitations — but the consequences were unavoidable. Children stopped studying at night. Refrigerated food spoiled. Residents could no longer rely on electrical devices such as mobile phones.

It also impacted their earning ability. Munzer’s wife, Ruba, who ran a small business selling milk and cheese sourced from her family’s sheep and cows, could no longer process these goods without access to a fridge. She began selling raw milk to a middleman who processed it outside the village, reducing her profit margins at a time when her family was already struggling.

90% of Syrians live below the poverty line, struggling to meet basic needs.

Limited access to power has also contributed to rising food insecurity in Khirais and across the country. As Syria largely relies on groundwater for drinking and irrigation, power-operated pumps are needed to ensure a steady water supply. However, without power, farmers like Munzer and Ruba are left scrambling.

Combined with other factors, this has resulted in an estimated 12 million people — more than half of Syria’s population — being food insecure, with 2.5 million facing extreme food insecurity.

Unable to cope with the lack of electricity, a few households in Khirais purchased generators to provide backup power. In addition to being costly, diesel fuel used for generators is refined from crude oil. It produces harmful emissions which pollute the air, water, and soil and contribute to climate change. And studies show it contributes to cancer development and adverse cardiovascular and respiratory health effects.

A solar panel installed atop a community centre in Khiras is providing village residents with access to electricity 24/7.

Introducing renewable energy

As the effects of climate change were only set to worsen, community members worked together to find a sustainable solution to their most pressing problem. Knowing that solar power would solve their energy shortages and create positive effects in their community, residents began exploring this possibility with the support of the Aga Khan Foundation in Syria. Solar panels had previously been financially out of reach to the residents of Khirais. However, the discussions with the Aga Khan Foundation led to a successful partnership.

In February this year, the Aga Khan Foundation in Syria installed solar panels on the roof of the local community centre. Community members established a cooperative, with all 24 households in Khirais joining as members, each contributing 500 Syrian pounds ($0.20 USD) monthly as maintenance fees.

Solar energy allows households to receive one kilowatt of electricity per hour — enough to light their home, keep their refrigerator running, and power other essential electrical devices.

Because we have electricity now, I’m working more hours and producing more products … [and] I can get more revenue.

In recent months, this solar panel has transformed life in Khirais. Ruba, whose fridge is now powered 24/7, began processing milk and cheese again, eliminating the need for a middleman.

“Because we have electricity now, it has increased our working hours and shelf life of the products,” Ruba said. “Now, I’m working more hours and producing more products … [and] I can get more revenue.”

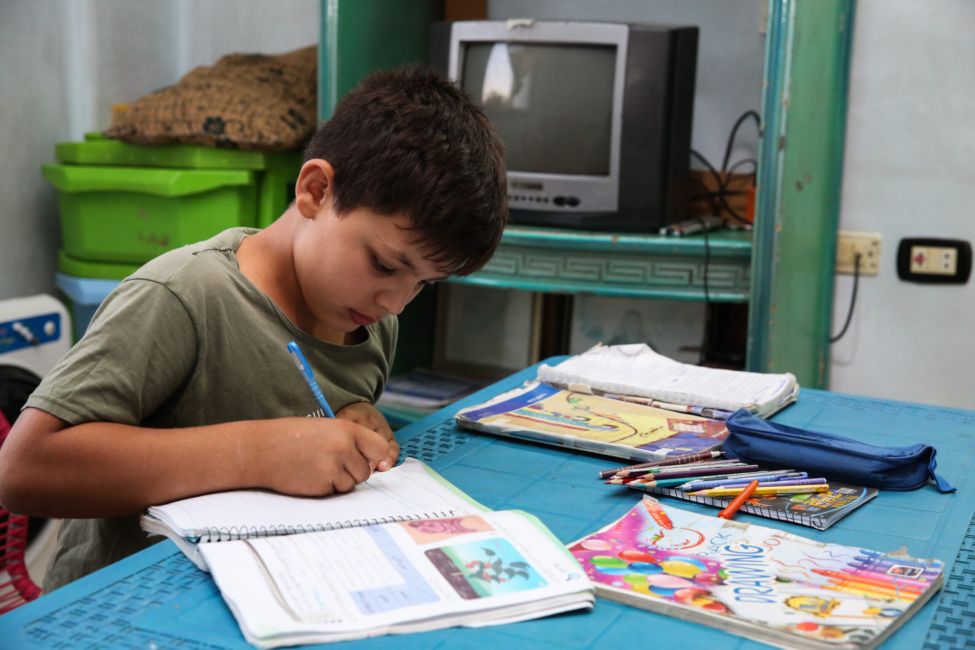

Her nephew, Hayderah Zidan, 11, who has lived without reliable power for his entire life, is happy seeing the recent changes in Khirais.

“The biggest difference is that we can use the light to study,” said the sixth grader, who now helps his family farm when he returns from school and begins studying after the sun has set.

He also shared another perk: “I can also watch TV whenever I want, and not just when we have electricity!”

Expanding solar access for communities in Syria

Solar energy is vital in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, which helps mitigate climate change. When communities have access to this clean energy, as they now do in Khirais, it increases their climate resilience, enabling them to better prepare for, recover from, and adapt to climate change.

Since 2021, the Aga Khan Foundation in Syria has supported over 3,400 households to access solar-powered water pumps. These pumps, which replace diesel generators, are used for irrigation. When farmers can irrigate their land sustainably, their families benefit through improved food security and economic livelihoods.

Hayderah Zidan, 11, who has lived without reliable power for his entire life, can now complete his homework late at night.

In addition to improving the quality of life in Khirais, solar energy has also eliminated the need for residents to use kerosene, commonly used as a light source in the evenings. Kerosene, a fossil fuel, creates carbon emissions and can cause health problems such as asthma, heart disease, strokes, lung disease, and lung cancer.

Community initiatives like Khirais’ solar panel tap into Syria’s high potential for solar energy, enabling people to shift away from fossil fuels, which will reduce emissions, provide decentralised energy, reduce air pollution, and enable vulnerable communities to deploy cost-effective energy solutions.

“[Solar energy in Khirais] is a success in terms of covering the whole village,” said Azizmamadov. “Every household in the village, including public spaces, has electricity for 24 hours [and] the community is managing the system quite well.”

With residents of Khirais reporting a significant improvement in their quality of life and an increased ability to expand agricultural activities, the Aga Khan Foundation is seeking to build on the success of this pilot to promote renewable community-led solutions across its programmes to address climate challenges while also creating economic opportunities. The organisation plans to replicate the solar project in ten villages annually, each with 50 to 250 households.

Moreover, the Aga Khan Foundation in Syria has supported nearly 160 microbusinesses in receiving financial support to install solar systems with up to four kilowatts of capacity. These solar systems help small business owners continue operating and enables them to retain jobs while eliminating fuel expenses and the need to rely on diesel generators.

The Aga Khan Foundation has also been supporting community initiatives in Syria to solarise streets and public spaces such as parks. Often, community members use these spaces to gather and host celebrations — creating an unanticipated, positive outcome of community-building and solidarity.

“It actually decreases tension when everyone has electricity,” Azizmamadov said. “It contributes to social cohesion, friendship, and people supporting each other more in the community.”

Words by Jacky Habib, photos by Ali Shaheen.

Jacky Habib is a Nairobi-based freelance journalist reporting about social justice, gender, and humanitarian issues. Her work has been published by NPR, Al Jazeera, VICE, Toronto Star, and others. Read more at www.jackyhabib.com.

Related News & Stories

Rebuilding Syria: How AKF is supporting entrepreneurs to revitalise the economy

A cut above: Meet Areej

Syrian youth design their future

Back to school: Meet Sedrat

Educating girls amid crisis

Support our work Your donations are helping us build a future where we all thrive together.